Bottom Up Beekeeping (372)

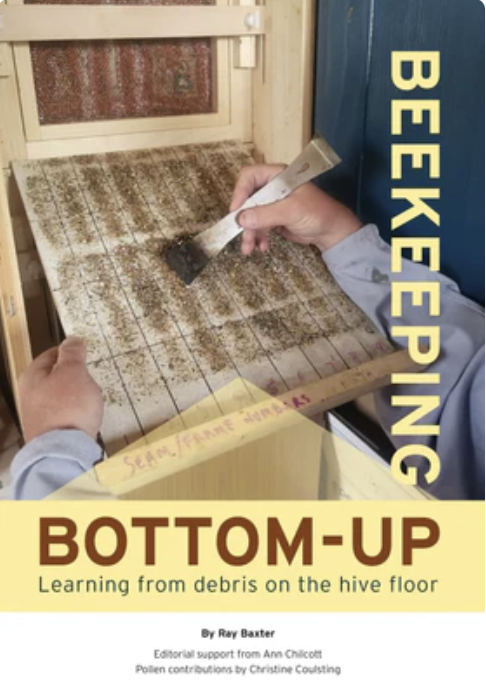

What can the hive floor reveal about colony health? Scottish beekeeper Ray Baxter explains how studying hive debris—from pollen and wax to Varroa fragments, aka bottom-up beekeeping—can guide better management decisions and deepen understanding of honey bee biology.

In this episode of Beekeeping Today Podcast, Jeff and Becky welcome Scottish beekeeper and author Ray Baxter to explore an often-overlooked source of insight inside the hive—the debris on the bottom board. Ray explains how careful observation of wax flakes, pollen, Varroa fragments, chalkbrood remains, and other materials (aka bottom-up beekeeping) can reveal colony health, brood cycles, forage history, and stress factors without opening the hive.

In this episode of Beekeeping Today Podcast, Jeff and Becky welcome Scottish beekeeper and author Ray Baxter to explore an often-overlooked source of insight inside the hive—the debris on the bottom board. Ray explains how careful observation of wax flakes, pollen, Varroa fragments, chalkbrood remains, and other materials (aka bottom-up beekeeping) can reveal colony health, brood cycles, forage history, and stress factors without opening the hive.

Drawing on years of microscopy and time-series sampling, Ray shares how studying debris transformed his own beekeeping and inspired his book Bottom-Up Beekeeping. What began as a classroom curiosity with students evolved into long-term research that now tracks seasonal colony patterns and informs more precise hive interventions, including targeted Varroa treatments and identifying brood breaks.

The conversation also highlights practical steps any beekeeper can take—such as photographing debris regularly, cleaning inspection boards consistently, and using simple tools like a smartphone or microscope to deepen understanding of colony biology. Ray emphasizes that debris analysis doesn’t replace inspections but adds another valuable layer of information to guide better decisions and reduce unnecessary disturbance to the bees.

Whether you’re a new beekeeper curious about IPM boards or an experienced beekeeper seeking deeper biological insight, this discussion opens a new perspective on what the hive floor can teach us about colony survival, nutrition, and seasonal change.

Websites from the episode and others we recommend:

-

Ray's Book on Amazon: https://amzn.to/4rdp0nH

-

Ray's Book at Northern Bee Books: https://www.northernbeebooks.co.uk/en-us/products/bottom-up-beekeeping-baxter

- Ray's Instagram Page: https://www.instagram.com/bottomupbeekeeping

- Project Apis m. (PAm): https://www.projectapism.org

- Honey Bee Health Coalition: https://honeybeehealthcoalition.org

- The National Honey Board: https://honey.com

- Honey Bee Obscura Podcast: https://honeybeeobscura.com

Copyright © 2026 by Growing Planet Media, LLC

______________

Betterbee is the presenting sponsor of Beekeeping Today Podcast. Betterbee’s mission is to support every beekeeper with excellent customer service, continued education and quality equipment. From their colorful and informative catalog to their support of beekeeper educational activities, including this podcast series, Betterbee truly is Beekeepers Serving Beekeepers. See for yourself at www.betterbee.com

This episode is brought to you by Global Patties! Global offers a variety of standard and custom patties. Visit them today at http://globalpatties.com and let them know you appreciate them sponsoring this episode!

As a beekeeper, you want products that benefit you and your bees. When you choose Premier Bee Products, you choose hive components that are healthier for bees and more productive for you. Because we believe that in beekeeping, details make all the difference. Premier Bee Products: Better for bees. Better for beekeepers. Use promo code PODCAST for 10% off your next online order.

APIS Tactical is a beekeeping brand focused on innovation. We create a wide range of gear for beekeepers of all types—whether you’re managing a few hives or working bees every day. We combine science and artistry to create purposeful, hardworking gear. We’re here to help you care for your bees with confidence, so you can focus on what matters most—your hive.

Thanks to Strong Microbials for their support of Beekeeping Today Podcast. Find out more about their line of probiotics in our Season 3, Episode 12 episode and from their website: https://www.strongmicrobials.com

HiveIQ is revolutionizing the way beekeepers manage their colonies with innovative, insulated hive systems designed for maximum colony health and efficiency. Their hives maintain stable temperatures year-round, reduce stress on the bees, and are built to last using durable, lightweight materials. Whether you’re managing two hives or two hundred, HiveIQ’s smart design helps your bees thrive while saving you time and effort. Learn more at HiveIQ.com.

Thanks for Northern Bee Books for their support. Northern Bee Books is the publisher of bee books available worldwide from their website or from Amazon and bookstores everywhere. They are also the publishers of The Beekeepers Quarterly and Natural Bee Husbandry.

_______________

We hope you enjoy this podcast and welcome your questions and comments in the show notes of this episode or: questions@beekeepingtodaypodcast.com

Thank you for listening!

Podcast music: Be Strong by Young Presidents; Epilogue by Musicalman; Faraday by BeGun; Walking in Paris by Studio Le Bus; A Fresh New Start by Pete Morse; Wedding Day by Boomer; Christmas Avenue by Immersive Music; Red Jack Blues by Daniel Hart; Bolero de la Fontero by Rimsky Music; Perfect Sky by Graceful Movement; Original guitar background instrumental by Jeff Ott.

Beekeeping Today Podcast is an audio production of Growing Planet Media, LLC

** As an Amazon Associate, we may earn a commission from qualifying purchases

Copyright © 2026 by Growing Planet Media, LLC

372 - Bottom Up Beekeeping

Anna Buckley-Schoelzel: Hello. This is Anna Buckley-Schoelzel from Buckley's Bees. I'm from Southwest Missouri, and we're here at the North American Honey Bee Expo, and this is Beekeeping Today Podcast.

[background music]

Jeff Ott: Welcome to Beekeeping Today Podcast presented by Betterbee, your source for beekeeping news, information, and entertainment. I'm Jeff Ott.

Becky Masterman: I'm Becky Masterman.

Global Patties: Today's episode is brought to you by the bee nutrition superheroes at Global Patties. Family-operated and buzzing with passion, Global Patties crafts protein-packed patties that'll turn your hives into powerhouse production. Picture this: strong colonies, booming brood, and honey flowing like a sweet river. It's super protein for your bees, and they love it. Check out their buffet of patties, tailor-made for your bees in your specific area. Head over to www.globalpatties.com and give your bees the nutrition they deserve.

Jeff: Hey, a quick shout-out to Betterbee and all of our sponsors whose support allows us to bring you this podcast each week without resorting to a fee-based subscription. We don't want that, and we know you don't either. Be sure to check out all of our content on the website. There, you can read up on all of our guests, read our blog on the various aspects and observations about beekeeping, search for, download, and listen to over 300 past episodes, read episode transcripts, leave comments and feedback on each episode, and check on podcast specials from our sponsors. You can find it all at www.beekeepingtoday.com. Hey, everybody. Welcome to the show. This is going to be a fun one. Becky, good to see you.

Becky: Nice to see you too. It's been a little while, Jeff.

Jeff: Yes. Did you do any beekeeping on that cruise?

Becky: There was very little beekeeping. I did find a bee in the ocean on the beach. I see it all the time. Beekeepers might agree with me. It's really often that when you're doing a walk on the beach that you see a honeybee who's landed there, and it's their final destination.

Jeff: Oh, when they're collecting salts or anything?

Becky: No. It wasn't there doing any work that I could tell. It was just there. Maybe they land there, and then a wave takes them on, and then it's over. No, I've seen a lot of bees in the sand. Yes.

Jeff: I'm so eager to get started in talking about your cruise. I forgot to thank Anna for that fantastic opening from Missouri.

Becky: Anna is a pretty special person. I've got a secret about Anna that's not so secret, but it's really fun news. She entered some beautiful photos in the NAHBE competition. One of them, she submitted to Bee Culture. That photo is going to be put onto the cover of Bee Culture, the March issue.

Jeff: Fantastic.

Becky: It would be this month, right?

Jeff: March should be next month, but that's all right.

Becky: Next month?

Jeff: Yes.

Becky: Okay. Anyway, look for that because she's got some amazing talent when it comes to bees.

Jeff: She certainly does. Thank you, Anna, for that opening. You were so excited about giving this opening while we were at the North American Honeybee Expo. It's great to be able to use it. Apologies for not thanking you when we started the episode. Becky, we have a great question from a listener today. This is for our Hive IQ Hive Tool promotion, where a listener submits a question, we read the question, or we play the question on the air, and then you and I get the chance to answer it.

Becky: Sounds good.

Jeff: This question is from Doug, and let's listen to it right now.

Doug Koch: Hello, my name is Doug Koch. I'm a backyard beekeeper in Winchester, Virginia. One of the things that I have rarely heard about is how do we tell beekeepers how to get out of beekeeping? We speak so much about how to get into beekeeping, how to become better, but there are times, and we've heard high numbers of 50% to 80% of people after two or three years who get out of beekeeping. What is the proper ethical way for people to stop beekeeping?

Should they burn their equipment, take it to a landfill, or leave it in their backyards, which I see often being done, which I don't think is the proper way. If you have any suggestions on how to help people with this, it would be greatly appreciated. I think it would help all beekeepers.

Becky: That is a good question. I want clarification. Is Doug saying we approach people and say, "You should get out of beekeeping," or is he trying to handle what to do, support for those who've made that decision on their own?

Jeff: Let's answer both because we probably all have, at some point, been in bees for a couple of years. You see, that person really shouldn't be keeping bees, and how should I tell them not to keep bees? Then helping somebody who's, this time of year is a very challenging time of year. Many colonies do not make it through the winter, whether it be Varroa or whatever reason, and the owner is sitting there with a bunch of empty equipment, and if they decide they don't want to stay in bees, what do they do with that equipment? That's a great question.

Becky: It is a good question. I have a hard line on frames. I don't think they should pass their frames on to anybody, regardless of what's in them. If they've got frames and foundation that they haven't put into a colony, fine, but anything that was in that hive that didn't make it, I say you bundle it up, and you dispose of it, and don't try to reuse frames. That's my line.

Jeff: I agree with you 100%. The frames are a mess to begin with, and trying to clean them up and give them away is just inviting trouble for everybody. It is best to put it in a plastic bag so it can't be disturbed, and then dispose of it, take it to the dump, or, if you have the ability, take it out back and bury it with a backhoe. My neighbor used to have a backhoe. That's the only reason why that came to mind.

Becky: I think that's illegal where I live, but okay.

Jeff: He buries so many different things in his backyard, I'm afraid to look at his backyard.

Becky: Check local restrictions first. As far as the equipment is concerned, honestly, that's where I love the stay in touch with your beekeeping organizations. I know we've had a lot of people would try to donate their equipment to the University of Minnesota. Sometimes we were able to accept it, but a lot of times we suggested that they push that forward to a beekeeping group because they're going to be able to disinfect, sanitize those boxes, and put them to good use either through having somebody purchase them, maybe, or maybe volunteering for one of their other programs like their teaching apiary.

Jeff: Giving away used equipment is very challenging for the disease issues. We've already talked about the frames, the boxes, and everything. If it's a brand new box, of course, I would donate it to the local club, like you said, for their learning apiary, or even maybe a new beekeeper if it's brand new. If it's a used box, I'd be hesitant to give it to anybody, and I'd almost probably destroy the box. I don't want to inadvertently transmit something.

Becky: One-year used, two-year used, five-year? What's your cutoff?

Jeff: [chuckles] I don't know.

Becky: Three months used?

Jeff: Three months used would probably be fine. Often, it would depend on, quite honestly, how the colony died out. I'd be honest with myself and to the person. I've taken stuff, and I've scorched it with a blow torch and had success with it. There's other times I just don't feel comfortable doing that. I would be careful giving stuff away, seeing people with an empty colony in the backyard, or an empty hive in the backyard. That's a hard thing to do. If I saw that, I would go to that owner and ask them if they want me to take care of it, and then I would dispose of the colony. Just keep it from being a nuisance.

Becky: Honestly, because it will attract swarms. I just read something about swarms. Up to 50% of the Varroa leave a colony with the swarm. Those swarms don't have a great opportunity to get a clean start. If they're going into used equipment and they're not being cared for, it is a recipe for disaster.

Jeff: To Doug's first part of his question, how do you tell someone to get out of bees if they shouldn't be in the bees? That's a challenge. I'm a person who always believes being direct with somebody would be the best thing to do.

Becky: Isn't that what people do on social media? Isn't that where you really get that anger out and tell people to get out of beekeeping? Not recommended, everybody. Let's be civil. Let's be nice. [laughs] There's getting out of beekeeping, but there's also making that suggestion, "Have you thought about getting a mentor?" Maybe there's that little bit of intervention that could make the difference in their beekeeping experience.

Jeff: Sometimes someone is just looking for help, and they don't know how to ask for help. I think what you recommend is a fantastic first step is ask if they need help with their bees.

Becky: There you go.

Jeff: All right, coming up on this episode, we have an author, Ray Baxter, talking about what you can find on the bottom board. Ray will be with us right after these words from our sponsors.

Betterbee: For more than 45 years, Betterbee has proudly supported beekeepers by offering high-quality, innovative products, providing outstanding customer service, many of our staff are beekeepers themselves, and sharing education to help beekeepers succeed. Based in Greenwich, New York, Betterbee serves beekeepers all across the United States. Whether you're just getting started or a seasoned pro, Betterbee has the products and experience to help you and your bees succeed. Visit betterbee.com or call 1-800-632-3379. Betterbee, your partners in Betterbeekeeping.

[background music]

Apis Tactical: This episode of Beekeeping Today Podcast is brought to you in part by Apis Tactical, a beekeeping brand focused on innovation. They use new designs, new materials, and new ideas to bring more joy to beekeeping. Apis Tactical creates a wide range of gear for beekeepers of all types. They use new designs, new materials, and new ideas to bring more joy to beekeeping. Their products are built with purpose, and they're already getting attention well beyond the US, with beekeepers in Europe discovering them through this podcast. If you're looking for well-made beekeeping gear from a company that understands the work, take a look at Apis Tactical. You can learn more at apis-tactical.com.

Jeff: Hey, everybody. Welcome back. Sitting around this great, big virtual Beekeeping Today Podcast table, we had to put in extra leads just to stretch all the way across the Atlantic to Scotland. We have Ray Baxter, author of the book Bottoms Up Beekeeping, and we'll talk about that shortly. Ray, welcome to the show.

Ray Baxter: It's a pleasure to be here, guys. Thank you for the invites. I'm looking forward to it.

Becky: I'm so excited about this discussion, Ray. You've done so much work about what's going on in that colony and their trash management, so I can't wait to talk about it. [laughs]

Jeff: Trash management practice. Ray's written a book about the debris on the hive that the colony produces. Ray, this is a fantastic book, but before we get into the book, can you tell us a little bit about yourself, and beekeeping, and your part of Scotland, and where in Scotland you are?

Ray: I live in the Scottish Borders. I'm about a mile away from the River Tweed looking south, very famous salmon fishing river in Scotland. I live and work on a four-acre organic smallholding. We grow and sell cut flowers. My wife does the flowers, and I do the bees. I started beekeeping about 15 years ago. I was working as a biology teacher at the time in a local high school. I'd worked for about 20 years as a science teacher. I wanted to introduce beekeeping into my lessons, or a little bit about bee biology. I started a local beekeepers course, and one thing led to another.

Little did I know how much that beginner's course would change things. At school with the students, I started introducing little bits about bee biology, and the students loved it, and I loved it. It set in process a bit of a positive feedback loop, really. Before long, we had a bee club in school, and that grew into manage finding a way to put beekeeping on the timetable. Then we became a pilot school for the Scottish Qualifications Authority. Before long, to date, there are about 25 high schools in Scotland offering beekeeping as a recognised qualification. We've got 13, 14-year-olds who are becoming independent beekeepers in their own right, which has just been the most wonderful thing to be part of.

There are some amazing teachers in Scotland doing the most amazing things with their students about beekeeping. Each year, as part of the beekeeping lessons, we would take the inspection board back to the classroom, and back to the lab, and we would count the number of Varroa mites we could see. We would have a discussion about our management plan for managing Varroa. One year, the students asked whether they could get out the microscopes and have a closer look at the debris. We did that, and they started asking questions that I couldn't answer.

At that point in time, that was six years ago now, I resolved that when I retired from teaching, I would start my own little research project where I would start trying to answer some of those questions and some of my own. It's been an absolute joy, after a couple of decades of teaching, to have a bit of space and time to start doing my own research. I really didn't expect or plan for this to become a book at all. It's about studying debris for my own interest, really, to see if studying debris could improve my own beekeeping practice. That was the aim for starting the study in the first place.

It very quickly grew arms and legs. I started sharing pictures of debris on private Facebook groups and got lots of questions and lots of support. Northern Bee Books got in touch and offered me the possibility of actually writing a book, which was blown away as an idea. They perform such an important role, helping people like me, who wouldn't see the light of the day normally, to have the opportunity and support to write a book like this, which has been just a great experience in my first year of retirement.

Becky: Oh, wow.

[laughter]

Jeff: You find that it's not so much a retirement, didn't you?

Ray: It's been very welcome, very unexpected, but very welcome thing to do.

Jeff: Your book is full of wonderful illustrations. That must have taken a lot of effort to coordinate all those and get them done. Did you have help with that?

Ray: No. It's been mostly me, and a microscope, and a bit of discipline. To be honest, the subject has just been so fascinating because each time I discovered something on the inspection board, I would then do a deep dive into the literature to try and better understand that. I would start writing people letters and emails. It just helped to fill a lot of dots for me in terms of bee biology, understanding honeybee biology, and my own beekeeping practice. It's been quite profound at times.

Becky: I want to make sure that we set the stage for the listeners because it is raised that time of year where we have a lot of new beekeepers listening. We have a lot of experienced beekeepers, but I want to make sure that the new beekeepers are a part of this. One of the things that you illustrate very clearly is you show a picture of a bottom board, a regular bottom board, what it looks like after a year, and it's just empty.

What you're talking about doing is collecting data on an IPM board or Integrated Pest Management board, where there's a mesh screen and then something underneath it to be able to track the debris. Since you wrote the book, you could probably explain that better than what I just did. Could you talk a little bit?

Ray: That was spot on because it's a ventilation screen that becomes the debris trap. Without the ventilation screen, the bees are very effective at reusing, recycling, or disposing of that waste material. We insert a ventilation screen, and that becomes a trap for debris that the bees can no longer access. That debris also provides us with an opportunity to monitor that, to look at how it changes over time, not just a snapshot inspection. We're looking at trends over time, which reveal so much about the colony biology, which I believe can help inform us and help increase the possibility of making positive interventions in the colony. It's adding another layer of understanding to what's going on inside the hive.

Becky: I mentioned to Jeff after we both had a chance to read the book that it wasn't what I expected. It was so detailed. The fact that you're providing this data from month to month to month about what's going on in that colony, that it was actually extremely revealing. I think you described that throughout the book really well yourself, that this has been a surprise along the way. You're seeing things in certain months that you maybe didn't expect to see. It's a very impressive compilation of information that goes really deep into just what can be found when you use that ventilation board or inspection board.

Ray: Yes. I'm still carrying on with the research. I thought when the book would be finished, the project would be finished, but I've seen no end to it. I've committed to myself to continue this for 10 years with as many hives as I can to try and get some real-time series data here to look at trends over a period of time for different colonies. It just says so much about what's happening above.

Jeff: I think it's really interesting that for many beekeepers, they're taught the IPM board is there to monitor Varroa drop. Before a treatment, during a treatment, after treatment, and what your mite drop, all of that. Teaching them to look at the debris from the perspective that you are at the detailed level, the things that you can find on the debris board. What are some of the things that you found on the debris board? In the debris that surprised you?

Ray: How long have you got, Jeff?

Jeff: You didn't find my missing keys or a hive tool or something like that, did you?

Ray: I'll go through half a dozen things. General brood-rearing debris and nest-building debris, whether that be fresh wax flakes, wax of different kind, recycled wax, wax mixed with propolis, and monitoring the shape and the size of that brood-rearing debris just says a great deal about the growth and the decline of the colony and everything that happens in between, really. I find lots of things like wax moth, Varroa, chalkbrood mummies and their reproductive structures, and some of the stress factors that are impacting on the colony, and how useful is that as a beekeeper to have a view on that before you've even actually opened the hive. You can measure those things and monitor that over time as well.

Something that really fascinated me is that the debris, a lot of the waxy propolis lumps, if you dissolve that wax, take a microscope and have a look at what's left, you will find lots of pollen. Lots of that pollen is actually from flowers that were in flowers six, seven months ago. It's giving you access to understand some of the nutritional and protein content of the food that bees are actually accessing. I did some analysis yesterday, the 28th is my sampling day for each month, and I was finding field beans and phacelia, things that haven't been in flower for a long time.

Also finding lots of different types of fungi and different types of plant material, and perhaps most surprisingly is the human man-made fibers and the quantity of those that are cropping up in the debris, which raises some important questions, I think, which could be a whole other podcast.

Jeff: You said you're finding these things in the pollen from flowers from six or eight months ago. What's the weather like right now in your part of Scotland?

Ray: It's been wet and grey and snowy and dark for, it feels like weeks at the moment. My bees haven't been outside for a long time, two or three weeks probably. There's very little in flower in Scotland at the moment, perhaps [inaudible 00:22:04], of course.

Jeff: What kind of hives do you maintain your bees in?

Ray: Teaching beekeeping in schools has meant that I've had to introduce students to different hives and different management regimes for different hives. Which means I've made a mistake when I started beekeeping. I bought a National, I bought a Langstroth, I bought a Smith hive, and I've got a combination of many, many different hives, which is really bad advice for any new beekeeper. When I retire, I resolve to change my beekeeping practice.

I'm planning to do beekeeping into old age, and I don't like lifting heavy boxes, so I've built myself a Slovenian-style bee house with eight hives. It also helps me to have identical hives as replicates, that I can control more for the purpose of my studies, which has been one of the motivating factors to move towards an AZ system.

Becky: The data you are collecting is really, there's so much of it. You said you collected data today, you collected the boards today. How long will it take you to process one colony's board?

Ray: I'd like to think I've got quicker.

[laughter]

When I started, it was probably about 10 days full-time to process the samples for that one month of debris. I would say it was 10 days processing and reading about it, so that was full-time. I would like to think I've got it down to about four days now, but that's a really detailed microscopic study of many, many different samples.

Becky: Is that for one colony then, or is that for multiple colonies?

Ray: I started with one colony, and this is growing now. I'm aware that there weren't as many replicates as I would like. The book is about one colony in my apiary. For sure, debris patterns will change according to bee breed and the whole set of other environmental variables. The observation itself has sparked my curiosity, and I'm now doing that with- I've got five hives that I'm monitoring at the moment, looking for trends over time.

Jeff: Differences, I suppose.

Ray: Yes, and there are some trends that, and over years as well, I'm into my third year now, so certain trends seem to be repeating themselves, which is really interesting, which is the motivation for wanting to continue this for another seven years. Lots can change in seven years, but it'd be great to have that data.

Jeff: Let's take this opportunity to take a quick break, and we'll be right back with Ray Baxter and get further into the hive debris.

StrongMicrobial: Beekeeping is demanding work. The last thing you need is equipment that can't keep up. That's why Premier Bee Products builds every frame and hive body in our South Dakota factories with one goal in mind: reliability when it matters most. From our beefy Pura Frames to our natural Prophyla Hive Bodies with rough interiors, we design for long life in the field and in the colony because we believe that in beekeeping, details make all the difference. Premier Bee Products, better for bees, better for beekeepers. Visit online at premierbeeproducts.com or call us today. Use promo code podcast for 10% off your next online order.

Premier Bee Products: Beekeepers, if you're looking for a smarter way to support colony health, take a look at Bee Bites from Strong Microbials. Bee Bites are a new protein patty made with spirulina, chlorella, and targeted probiotics designed to support nutrition without creating new problems in the hive. With 15% protein, Bee Bites are unique because they do not attract small hive beetles, a big deal if you've ever battled infestations during feeding. Strong Microbials has been supporting beekeepers and farmers since 2012, developing high-quality commercial probiotics and nutritional supplements you can trust. Learn more about Bee Bites and their full line of bee nutrition at strongmicrobials.com.

Becky: Welcome back, everybody. Ray, we need to talk more about data because you are not just weighing all of the debris, but you're also doing something as far as looking at the individual pollen grains you're finding. That's a big skill to be able to actually identify pollen. Was that hard for you to do?

Ray: Yes. It shouldn't really be any more complicated than being able to identify an orange or a pear or a banana because what you're actually doing is you're looking at the physical structure of those pollen grains as you do with fruit. There's a lot of learning goes into being able to identify a banana, or a pear, or an orange. Perhaps later in life, it becomes a little harder to go through that learning process. Is that making sense?

Becky: I've watched people early in life learn how to identify different kinds of pollen, and it wasn't easy for them either. It's a big skill to have. It's one of the reasons why pollen is still a little bit of a mystery to a lot of beekeepers, because just even being able to isolate it and to put it on a slide is the skill that I'm sure you've had to work on.

Ray: Yes. It has taken a huge amount of practice to be able to make successful identifications of those pollen grains. I've been helpful that I've had a published author, Christine Coulston, who's helped me and been my mentor with helping to identify different pollens. If I've been unsure, then I've got in touch with her, and she's helped me out. I've only become proficient at identifying pollens in my local area, really.

If you put me in a different part of the country, I would perhaps struggle a little bit more, but I've got to know what the pollens look like for the forage that exists in my area so I can identify. There are probably about 30 or so pollens that keep repeating themselves. I can quickly identify now through practice, and recognize those different shapes.

Becky: I'm hoping this is inspiring some of the other beekeepers, scientists out there who really want to do a deep dive and learn about what their bees are doing.

Jeff: Along those lines, what does an aspiring beekeeper who wants to get deeper into the debris, [chuckles] what kind of equipment would they need to consider? Obviously, what we call the IPM board or the screen bottom board. What else would the beekeeper need?

Ray: I think most beekeepers or all beekeepers are probably carrying a really effective tool in the pocket in the form of a mobile phone. I have no doubt that if Langstroth had a mobile phone when he wrote his seminal book, and he did mention debris in some of his publications, I have no doubt that he would have used a mobile phone to keep records about honeybee debris. He was a meticulous notekeeper. I'm confident he would have used that.

I would recommend to anybody who wants to start or is interested in finding out more about debris to take out their mobile phone and to take photographs of debris in two consecutive weeks, and make a comparison of the debris between those two images. They will see changes. Perhaps in the spring, they will see growth, and that will spark questions and curiosity.

Jeff: Doing those two consecutive photos, would they be cleaning off the bottom board in between?

Ray: Yes. That's what I decided to do. The key thing is consistency. I've chosen a 28-day sampling for myself, but I've got particular goals. People may have different goals and choose a weekly sampling schedule, and that's fine too. After each sampling schedule, I clean the debris board, start afresh, so I can make a fair comparison with the previous time period that I've sampled.

Becky: Ray, do you have any concerns of if beekeepers have a ventilation board and they're not cleaning the board regularly because of the fact that the bees on their own will clean it out, but you see what accumulates, and you've seen close up what's in there. Are there any warnings for beekeepers who decide to use that equipment but then don't follow up on cleaning the board?

Ray: Oh, definitely. The bees wouldn't choose to have that debris sat underneath their nest. I think there's a real health and safety risk for the honey bees in terms of upward contamination of various things, which could be harmful to the colony. Yes, I would strongly recommend cleaning the debris board on a regular basis.

Becky: Are you thinking at least once a month?

Ray: It depends which point of the year we're at because the debris changes a lot between the winter, spring, summer, and autumn. For the purpose of my study, I chose the 28-day sampling window, but in the summer, I have played around with that, and I think there's an argument to reduce that because there's so much debris build up in May and June. I have been concerned that potential risk through the buildup of debris. You leave it for any longer than that, and you'll suddenly get an explosion of mite populations living in the debris, breaking that down, and you'll get fungal growth, and different things will start happening. The debris will start moving.

Becky: It will start moving. When you're talking about mite populations, it's not Varroa, it's just all the other mites that are out there, correct?

Ray: Yes, the inspection board is effectively creating a bit of a food trap underneath the bottom of the hive that things can live on and make a good living there. Yes, it's probably a good idea to clean that away on a regular basis.

Jeff: Even in terms of honey bees will get down in there from neighboring hives and start rooting around in the debris. Yes, it's good to keep it cleaned off.

Ray: Yes, for sure.

Jeff: Would you recommend someone who's interested in this getting a microscope?

Ray: I would certainly recommend that people explore the idea of getting a microscope. The type of microscope that you should get is a much more complicated question because it depends on what the purpose of their study. Do they want to take photographs of debris? To what depth do they want to study? Do they want to identify pollen? Each of those questions would have a different answer. It's probably good to join a local microscopy club, and they will exist, or go on Facebook and join a microscopy group there, and just start asking those questions. It's a friendly community.

Jeff: I will add that for that microscopy, and it's a hard word for me to say, there's a lot of interest in that in the States here. I know in many of the conferences that we go to, there's often pre-workshops or post-workshops during the conference about microscopy. The speaker will bring microscopes, or a local university will bring microscopes. There's a whole session about how to use a microscope and go through it. I would suggest anybody who's interested in this try to find a conference that has a workshop in microscopy and go to it.

Our good friend of the podcast, Etienne Tardif, who's a beekeeper from the Yukon in Upper Canada, does a lot of microscopy work with his bees. I would say that's a growing area of interest in beekeepers, more than I can remember in the past.

Becky: They're a lot more accessible. It used to be that you had to go to a university or a school to find a microscope, and now you can order one. It's not as expensive as it used to be, I think.

Jeff: You have it the next day on my Amazon Prime.

Ray: Definitely. A real fun thing that's developing after writing the book, actually, is we've established in my local beekeeping community a local research group, a microscopy group, where there's half a dozen of us meeting every other month to try and answer our own questions about honeybees. That's just starting, but it's a really interesting spin-off of writing the book.

Becky: I would think that people who read your book really do want to get in touch with you and be a part of what you're doing. I would think that after you get through the book, there's a lot of incentive to get to know their own colonies more. Have people reached out to you and looked to you for more advice?

Ray: Oh, Becky, I can't even begin to explain how amazing this has been. I didn't plan to write a book. I ended up writing a book. I thought when I finished writing it, that would be the end of it. I really didn't expect what would then follow that. I get almost daily emails from different people and pictures of honeybee debris. It's just been wonderful to be part of and see other people start asking their own questions about honeybees and using debris as a tool. It's been wonderful to be part of.

Jeff: Is there anything that would raise a concern that would require a beekeeper's immediate attention if they found it in their debris tray?

Ray: There are things that are certainly of concern. The things that I've seen that have concerned me have been the chalkbrood infestation in a number of colonies. It seemed that the bees could actually manage that themselves, and they sorted that out themselves without any human intervention. If you have a colony that's being hit hard by wasps to actually see that damage in the debris and to see those bee battles playing out in the debris, you can begin to imagine what must be happening around the nest. Varroa, something that's really fascinating.

If you dissolve some of the bee debris, you can see the whole Varroa mite, but if you start dissolving the debris and start looking closer, you'll start to see lots of Varroa fragments in the debris, little bits of legs and little bits of exoskeleton, which is quite interesting. One example from last year is there was suddenly an absence of cappings. Something had happened. One week, there were hundreds of brood caps. The next week, it was blatantly obvious there were absolutely none. There was some kind of brood break. I wanted to ascertain for myself, is that colony a queen right colony?

At that point, I intervened, removed a frame, spotted some eggs, put it back, and that was my intervention at that point in time. Other ways that I've used the debris, for example, with Varroa treatment, I provide, or I have done in the past, treated with oxalic acid. Before I started studying honey bee debris, I would quite liberally add five mils to each seam. That's 10 seams of bees, that's 50 mils. Using debris, it's possible to locate exactly where that nest is. Looking at that cluster of debris, that debris pattern, I only needed to provide treatment to three seams of bees.

That's 15 mils of oxalic acid treatment, rather than what I was doing previously, which seems like a sensible thing to be doing, rather than overtreating the colony. Just as a small example of how that data can be used, of how the debris can be used. It's all about informing positive hive interventions for me. That's what I'm trying to use the debris for: to improve my chances of making positive hive interventions without opening the hive. It's not about replacing hive inspections. It's just about providing another layer of information to guide that practice.

Becky: Ray, I liked your discussion about how, when you were monitoring for mites, you recognized the fact that the treatment threshold didn't expect somebody to be digging through the debris and actually coming up with a little bit different number. You're finding yourself in an area where there aren't necessarily guidelines for the amount of information that you have in your hands, because most beekeepers don't know as much as you do about what's going on in their colony. I think you decided to not go ahead and do a mite treatment because you were going through, even though you knew maybe there were a few more in their colony than what the actual regular count would give you. Did that turn out okay?

Ray: Yes. That's a really interesting question, actually, because I was monitoring the Varroa drop month by month, and it was just under the recommended level for treatment according to the guidance for the national bee unit, which exists in the UK. I decided not to treat them. They requeened last year, and for the following 12 months, the mite drop has been negligible for that colony, and they've had no treatment whatsoever. I'm watching very carefully now, and I'll be really interested to see what happens over the next few months in the spring buildup. It'll be really interesting to see what happens there.

Becky: I also have a follow-up to that because you mentioned finding little mite parts, and it sounded like the bees maybe were going after the mites a little bit in grooming. May I ask you, your queen stock, what subspecies do you have, and do you have any special stock, or did you find yourself in a lucky position?

Ray: No. When I started beekeeping, I bought two colonies from somebody who lives nearby, the most aggressive bees that I've ever had. All of my stock comes from those two colonies of bees. I've never bought any bees in. I've just split and done a little bit of queen rearing over the years, and everything comes from those. I've not had them genetically tested or the local bees to this area, and they seem to do quite well.

Becky: Are they potentially Apis mellifera millifera?

Ray: They are potentially, yes, but I haven't

Becky: With that little reputation? [laughs]

Ray: Yes. They live up to that reputation quite well.

Becky: Now I understand the reason for monitoring the debris.

Ray: Exactly.

Becky: You get fewer stings a year, right?

Ray: Yes. It's always a good thing to aim for, isn't it? Yes.

Jeff: What would you recommend for a beekeeper who's wanting to start looking at their hive debris? What are the first steps they should consider?

Becky: They should buy the book, Jeff.

Jeff: The second and third steps, what would you recommend? The book is available directly from Northern Bee Books, and it is available on Amazon. That's where I got my copy.

Becky: What else do you recommend, Ray, besides the book?

Ray: A mobile phone for taking photographs for regular periods of time, whether it be a weekly series or a monthly series, which will very quickly help beekeepers identify different trends over time. That time series of data for me is really useful. I'm now into my third year, and as the years progress, it will be really interesting to see where the commonalities are and where the trends are for different months in terms of growth, decline, brew breaks, swarming, et cetera, and how that puts itself in the debris. For me, now that's part of becoming a better beekeeper is understanding without having to take the top off the hive and start disturbing frames.

Jeff: I know I grew up learning as a beekeeper, that the more you open a colony, the more you disturb it, the more production you take away from it. If you can find ways to understand what's going on in your colony without opening up and removing frames. I think every beekeeper is at one time or another accidentally killed their queen, or at least potentially did. Anything that you can do to not do that, and examining the hive tray is one example, I think, is a good tool to have in your back pocket.

Ray: Definitely. Often, the most important inspection is the one that we don't do.

Jeff: Most important one, that's for sure. If you could leave our listeners with just one last thought or one last consideration, idea from this book, what would that be?

Ray: The one thing I'd want people to take away is to simply start using debris and asking their own questions about the colony above and use that to inform their beekeeping practice, to look at ways to improve their beekeeping practice. If they make any great discoveries, then please get in touch and let me know. It'd be great to hear.

Jeff: You mentioned a Facebook group. Was that just local, or since this book is out, are you ready to open it up worldwide to have people reach out to you and email you directly?

Ray: I have an Instagram page called Bottom Up Beekeeping, which is part of the Instagram page. I'm not sure what the future holds for the Facebook page. Yes, it is growing, but I need to make some decisions about that, but I'm not quite there yet.

Jeff: I can understand that. Well, Ray, thank you so much for joining us today. You've given me a whole new, different way, after reading your book, a whole different way of looking at hive debris. I've always been fascinated, thinking there's got to be a story, but now I know there's definitely a story that I'm scraping away there, and I need to slow down and take a look at it. Thank you for joining us.

Ray: It's been an absolute pleasure. It's been a pleasure to do. Thank you for the invite, guys.

Becky: Thanks, Ray. I am confident that you're going to have a number of people contacting you after they read your book and following up. You really are starting a little bit of a beekeeping revolution. Great job, Ray.

Ray: Delight to be part of. Thank you, Becky.

[background music]

Jeff: That is fun to think that there's so much information in that bottom board that I'm scraping off. I should take more time to read it.

Becky: You've got another project. First, you have to buy two microscopes.

Jeff: [laughs]

Becky: I expect you to deliver on this. I think our listeners want a monthly report. Or we could connect with Ray again. Let's you off the hook.

Jeff: You know what? I like your second idea better. Let's connect with Ray on a regular basis and talk about what's on your bottom board.

Becky: Oh, I love that. Okay, that's the title.

Jeff: That's the title of our new series is What's on Your Bottom Board?

Becky: I will say, write that down. Write that down.

Jeff: I'm a trademark it right now.

Becky: Right now. I will say that the book surprised me enough, as far as just the detail and what literally is on the bottom board, that I think that there's enough to talk about for multiple episodes. When other beekeepers start looking on their bottom boards, boy, that's a whole new community that's being created. Good for Ray.

Jeff: I totally spaced on asking him about the microplastics and man-made materials. That was a whole different, fascinating topic that he discussed.

Becky: It was a whole big bummer. I'm glad we're not talking about it in this episode.

Jeff: Oh, yes. Yes, I hear you.

Becky: Let's get to it later, maybe.

Jeff: When it's sunnier outside and warm.

Becky: When it's sunnier outside and warmer, and maybe honey supers are being filled and all that. Then maybe we can talk about that serious subject again.

Jeff: That about wraps it up for this episode of Beekeeping Today. Before we go, be sure to follow us and leave us a five-star rating on Apple Podcast or wherever you stream the show. Even better, write a quick review to help other beekeepers discover what you enjoy. You can get there directly from our website by clicking on the Reviews tab on the top of any page. We want to thank Betterbee, our presenting sponsor, for their ongoing support of the podcast. We also appreciate our longtime sponsors, Global Patties, Strong Microbials, and Northern Bee Books for their support in bringing you each week's episode.

Most importantly, thank you for listening and spending time with us. If you have any questions or feedback, just head over to our website and drop us a note. We'd love to hear from you. Thanks again, everybody. I have nothing else to say.

Becky: [laughs] Please leave that in.

[00:48:03] [END OF AUDIO]

Bottom Up Beekeeping Biography

Are you interested in understanding your bees more and disturbing them less?

Learn how to use the debris from the hive floor as an indicator of colony activity and a way to interpret what’s happening inside and outside of the colony. This book is based upon a DIY research project about how the debris from honey bees changes over a year. Ray uses these observations for a deep-dive into the scientific literature to explain the debris and relates this to beekeeping practice. More than two hundred high quality images give a fascinating insight into life of a honey bee colony.

Ray Baxter’s passion for beekeeping started fifteen years ago when he was working as a biology teacher. His initial plan was to learn more about honey bees and share this experience with high school students in the biology classroom. This quickly developed from being an occasional lesson into an extra curricula bee club, to putting beekeeping on the school timetable as a Scottish National Progression Award (GCSE level) and supporting other schools with the development of their own beekeeping qualifications. It’s a journey that has been inspired by the enthusiasm of young people and the questions that they ask. In fact, the idea for this book came from a discussion with youngsters who were counting mites on the inspection board and who became side tracked by other finds in the debris.